The Handmade Village

- Ornamentum

- Sep 1, 2025

- 9 min read

by John Leroux

THE EARLY 1970S WERE A TIME OF DEEP SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHANGE in Canada, and especially so in New Brunswick. The era saw substantial economic improvements throughout the province, but it also witnessed diverging views on postwar progress, what it meant to be a connected citizen, and how material items held deeper consequence.

This was a time of opposites, and one would be hard pressed to find a place that represented this as much as Mactaquac, New Brunswick, a rural area fifteen kilometres upriver from Fredericton. Here, the recently completed Mactaquac hydroelectric dam—the largest in the Maritimes—buttressed the St. John River, while nearby a group of young artisans and craftspeople opened one of Canada’s most celebrated craft enterprises: Opus Craft Village (fig. 1). Fuelled by the growing interest in the handmade and a back-to-the-land spirit driven by the emergent counterculture, the fine craft artisans of Opus and their story is a fascinating tale of a creative destination briefly glowing bright and extinguished far too soon.

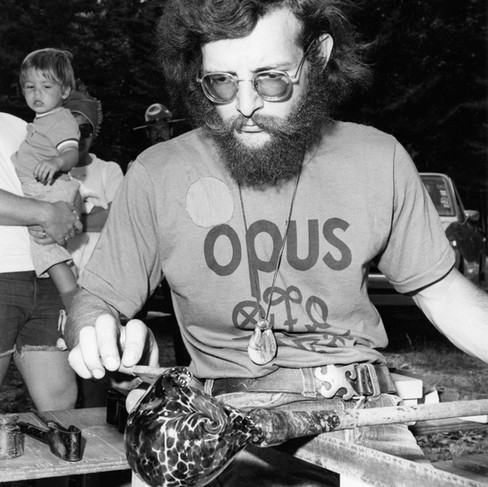

The sweeping headpond lake created by the Mactaquac dam spurred new recreational and cultural destinations in the area, primary of which was Mactaquac Provincial Park in 1970. It quickly became a popular tourism destination for visitors from across Canada and the United States. With swimming, camping, golf, and beautiful woodland and waterfront trails, the park was a significant draw. This, added to the charm and affordability of the area, brought two young potters together to establish a full-time ceramics studio nearby in 1971. Allan Crimmins (1943-2020) and Bill Norman (b.1942) launched Keswick Ridge Craftsmen—named after the community adjacent to Mactaquac—and their networks, work ethic, and quality of work saw their audience quickly grow. Crimmins (fig. 2) had been head of the New Brunswick Handicrafts Branch since 1969 and a ceramics educator at the Fredericton-based New Brunswick School of Arts and Crafts (now the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design), where Norman also taught since 1965. American-born glassblower Martin Demaine (b.1942) joined the duo in 1974, bringing with him the first one-person hot glass studio in Canada (figs. 3 & 4).

Fig. 3 (left): Onlookers watching glassblower Martin Demaine sculpt a hot blown glass vessel at Opus Craft Village, 1977. At the time, Demaine's studio was the only one of its kind in Canada (PANB #P225-10457). Photo courtesy of the New Brunswick Provincial Archives. // Fig. 4 (right): A 1977 handblown glass vase by Martin Demaine, 9.5cm x 8.25cm x 8.3cm. Collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery; gift of Gary H. Stairs. Photo: John Leroux.

The annual Mactaquac Handcrafts Festival began in 1972. In ensuing years, people camped overnight at the park gates to ensure they would be among the first to get their hands on the artisans’ wares. By the mid-1970s, tens of thousands of festival attendees bought New Brunswick craft items (fig. 5). With audiences hungry for locally handmade objects, Crimmins devised a full-time craft village at Mactaquac based on successful precedents in Ireland and Norway. Together with Demaine, Norman, and four other craftspeople, Opus Craft Village officially opened on June 21, 1975, and New Brunswick’s fine craft aficionado Premier Richard Hatfield cut the ceremonial ribbon in front of an enthusiastic crowd of 500 onlookers.

Before the grand opening, Demaine asserted in the Saint John Evening Times-Globe: “New Brunswick is an exciting place to live in terms of crafts. We’re building the Village here in the right climate and atmosphere.” He stated that the philosophy behind Opus was to create an understanding of how crafts are made and to promote craftsmanship in the province. Visitors and buyers were welcome to tour each of the studios and see first-hand how the wares were made and meet the makers in a real, workshop setting. Understanding that too many onlookers could also hamper the rhythms of production, plus to raise funds, they charged adults a studio entrance fee of one dollar. In the spirit of bringing the makers and the public together in a meaningful, participatory way, Demaine explained: “In addition to just watching the craftsman at their work, the public will be able to put their hand to the potter’s wheel or blow some glass as the studios will be open for the public’s use several days during the summer. On these days entrance will be free and all materials will be supplied.”

The artists shared ownership of the land on a prominent site across the main road from Mactaquac Provincial Park. They also helped construct or refurbish a campus of studio buildings. The two largest wood-frame buildings clad in vertical boards housed the display centre/shop (fig. 7) and the pottery studio. These were the Village’s visual anchors and stood closest to the road. Behind these structures was Demaine’s smaller shingled studio, the Mactaquac Glass Works, housed in a former barn rescued by the artists and moved to the Opus site. Behind the glass studio were the ironwork/blacksmith shop (fig. 6) and a house used for both living quarters and the candle studio. The pottery studio with its giant kiln (fig. 8) became one of the most tangible symbols to New Brunswickers of the modern craft movement: a bold wooden volume with steep rooflines that said something new and different was happening inside its walls. The pottery studio’s architectural impression was not unlike Maine’s famed Haystack Mountain School of Crafts which opened in 1961, albeit a simpler New Brunswick version.

In addition to Crimmins, Norman, and Demaine, the original Opus craftspeople included Martin’s wife Sue Demaine (wax candles), Bill Graff (ceramics), David and Barbara Murphy (leatherwork) (fig. 9), Don Pell (blown glass and ironwork), Jane McLellan (wax candles), Paddy Ormiston (glass blowing), and apprentices, among others.

An “opus” is a creative artistic work, often with several components; Opus Craft Village’s logo embodied the multiplicity of materials and artisans’ hands: a boldly graphic eight-pointed star, whose tips were alchemic symbols for materials such as tin, earth, and glass. To manage this diversity of people and practices, Crimmins insisted on regular and open meetings of the artists, communal lunches, and a general sense of collegial respect. Opus was run on co-op principles based on shared values and group decisions. Crimmins recalls:

We all sat on the boardwalk and ate lunch together, and there was a daily interchange between the studios, but at the end of the day, Marty [Demaine], Bill [Norman], and I made the decisions. The thing worked beautifully. We didn’t wholesale anything; we sold everything right there. I suppose it was entrepreneurial, but it was so much fun. We got so caught up in doing it that it was almost an act of creation in another sense. We enjoyed the whole experience. The fact that it made money was almost insulting.

Demaine concurred: “The Village atmosphere solves many of our problems. It provides stimulation. It makes marketing our work a lot easier. And our materials are less expensive because we buy them together.” The opening of Opus was an optimistic time for the members, and the growing audience for buying fine craft was not lost on the burgeoning studios (fig. 10). At the time, Demaine noticed a big change in the concept of crafts since the start of the 1970s. He felt, “People now think it is a necessity to have crafts in their homes and there has been a move to buy direct from the craftsman and not from the gallery.”

Open year-round, Opus Craft Village was a commercial offspring of the fine crafts foundation established over the previous four decades by the renowned Kjeld and Erica Deichmann, whose glazed ceramics developed an international reputation from their home and studio in rural southern New Brunswick—a studio that was open regularly to clients, the curious, and casual drop-ins.

Of note was that almost all the craftspeople and apprentices at Opus lived in Mactaquac/Keswick Ridge rather than Fredericton, a 20-minute commute away. Many rented rooms from local farmers and others. Ken and Sheila Moore, residents of Keswick Ridge since 1972, rented rooms in their house to Opus craftspeople and apprentices. Sheila reminisces, “It was an amazing community. When we moved there, it was a rural farming region, but there was a growing intellectual presence as university professors and graduates were moving here, looking for something outside the city and embracing the rural lifestyle. That was the beginning of a major change, and Bill Norman and Allan Crimmins had a vision for something way bigger than their own pottery studio.”

Fig. 8 (left): Allan Crimmins loading the large pottery kiln at Opus Craft Village, April 1976 (PANB #P354-188-18A). Photo courtesy of the New Brunswick Provincial Archives. // Fig. 9 (right): 1970s handmade leather briefcase by David Murphy, whose Middle Earth Leather Works workshop was at Opus. Collection of Ken Moore. Photo: John Leroux.

Opus and its open studios affected the spirit of the community, and attitudes throughout the whole province incorporated new creative ideas and artistic experimentation. Moore explains:

After a few years, once Opus was established and became very much a part of the community, local farmers who one might think didn’t care about art would drift in every once in a while, to see what was going on. The next thing you know, they’d ask ‘Can I try blowing glass?’ This, to me, was the most significant thing that they did in terms of the local community. For the locals, it broadened their minds, they were trying out things they never would have experimented with.

Ken Moore wholeheartedly agrees on the building of trust: “It had the effect of blending the newcomers and the old farming community in a very positive way. . . Before you know it, it [became] more of a community than it might once have been.”

With annual sales of their Opus-made crafts grossing $100,000–a substantial sum half a century ago–the Village’s future seemed secure. Don Pell feels that working at Opus “was more exciting than we ever thought. We had an energy to make it work, and we did!” When Queen Elizabeth visited New Brunswick in 1976, her official gift from the province was a set of six hand-blown glass goblets made at Opus. At its peak, Opus Craft Village housed seven craft studios and 25 craftspeople. But like all good things, it wouldn’t last. Gail Crawford, in her 2005 book Studio Ceramics in Canada, succinctly laid out the demise of Opus Craft Village; a not-so-rare instance where artistry and business do not always coexist favourably:

The village became a much bigger project than any of them had imagined, however, and managing it and parenting the tenant-craftspeople took more and more time from their own studios. Thinking the place needed a businessman to run it, they sold it after a few years. ‘We made a huge mistake,’ Crimmins acknowledges now. ‘We realized later that this craft village was not the sum total of the bricks and mortar we put in it, but the sum total of the people we had involved in it.’ In other hands, it did not last long, and the magic disappeared.

After Opus was sold to a local businessman in 1978-79, challenges arose between the artists and the new owner, and the original craftspeople left. Apprentices took over many of the studios, but their lack of experience and clients made this an untenable arrangement. As Don Pell maintains, “As soon as you lose the big excitement, it changes.” By 1983, Opus Craft Village had closed its doors.

It was also the end of an era, for the next decade saw changes in the types of fine craft that appealed to the public. But what of the original Opus artisans? For many, it was a stepping stone to longer careers in craft. Martin Demaine has work in the permanent collections of the Canadian Museum of History and the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Massachusetts Institute of Technology hired him as a researcher in the early 2000s and later invited him to teach in their glass lab, becoming Artist-in-Residence from 2005 to today. Don Pell continues to operate a thriving wrought iron and glass studio in Saskatchewan. The Murphy leather studio continued for many years in Keswick Ridge. Allan Crimmins ran his successful Crimmins Pottery studio for decades in southern New Brunswick, and it is now run by his daughter, clay artist Elizabeth Crimmins.

Beyond the handmade creativity Opus Craft Village offered, and the innumerable gifts of fine craft purchased there that were sent all over the world, Sheila Moore feels that the greatest gift Opus offered “was a sharing and an understanding of different ways of life.”

____________

John Leroux, PhD, ONB, has practiced in the fields of art history, architecture, visual art, curation, and education and is currently the Manager of Collections and Exhibitions at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of Ornamentum magazine. To purchase the issue or subscribe, head to our store.

Comments